MAMT||Museo Mediterraneo dell' Arte, della Musica e delle Tradizioni (EN)

|

05 March 2022

Iniziative (EN) -

MAMT – Mediterranean Museum of Art, Music and Traditions

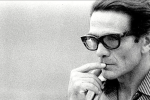

A great influx of visitors - in compliance with Covid 19 rules - and of links and contacts on the multimedia platform of the Museo della Pace - MAMT for the centenary of Pier Paolo Pasolini's birth.

A great influx of visitors - in compliance with Covid 19 rules - and of links and contacts on the multimedia platform of the Museo della Pace - MAMT for the centenary of Pier Paolo Pasolini's birth.

"An anniversary that coincides with the madness of the war in Ukraine," said President Michele Capasso, "which is why Pier Paolo's message and values are more relevant than ever. Today we were in Scampia, in front of the mural depicting him: a way of paying homage to one of the most important intellectuals of the 20th century".

President Capasso recalled that Pasolini was born in Bologna on 5 March 1922.

He was a controversial author, scandalous for a long time in the Italy of his time for a homosexuality that he did not hide, 'cursed' for the circumstances of his tragic death (he was murdered at the Idroscalo di Ostia on the night between 1 and 2 November 1975), the dynamics of which have not been fully clarified, but also marked by a constant fascination with the sacred dimension (his Vangelo secondo Matteo is perhaps the most beautiful film ever made on the life of Jesus).

One hundred years from his birth is one of those round anniversaries," continues Capasso, "that bring attention and reflection to an author, and even more so to an author like Pasolini, on whose work a critical production has flourished over the years that is unparalleled by that of any other 20th-century writer.

An anniversary like this is an opportunity to ask ourselves some questions.

What is Pasolini's originality?

What are the reasons for his importance?

How is he still relevant today?

These are questions that we must try to answer without rhetoric, avoiding the temptation of hagiography: Pasolini should be addressed and discussed, not necessarily approved of in everything he did or said. His originality is linked to the extreme versatility of his creative path: Pasolini began as a poet (Poesie a Casarsa, 1942), continued as a novelist (Ragazzi di vita, 1955), continued as a film director (starting with Accattone, 1961), wrote for the theatre and newspapers, was a literary critic and columnist. He also painted: and perhaps this is the only concession to amateurism in an artistic career in which he reached the highest peaks in every field in which he ventured. But his work should be read as a whole, without separating the different genres: then it truly appears as a great 'total' work, in which the different phases intertwine in an open and mobile creative discourse.

As for Pasolini's importance, no other writer of his era has left a trace, in the national experience and in our collective memory, similar to his, through his work and life. Pasolini's importance does not only concern literature and culture, but also Italian history, since he continued to deal with it, convinced as he was of the moral and civil responsibility of the intellectual. Although not without some ambiguities and personal idiosyncrasies, Pasolini was able to question himself about the present, to read the contemporary in relation to the past, and therefore to intuit the directions in which the future would have taken him. Without being a 'prophet': a definition so abused as to become a commonplace. Is Pasolini current? Because of his uncomfortable position, Pasolini was a great 'out-of-date' in his time. First, with regard to politics, he was a 'disorganised' intellectual, autonomous and independent of any ideological mortgage; Then, while, from the late 1950s onwards, the dimension of commitment was disappearing among Italian artists and post-modern culture was asserting itself as the bearer of a playful and playful idea of art (including literature), in Pasolini, on the other hand, Pasolini, on the other hand, persisted - and indeed seemed to intensify in the last phase of his work (think of the Scritti corsari and Lettere luterane, the unfinished novel Petrolio and even a shocking and disturbing film like Salò) - a tenacious desire to criticise consumer society, its false values and the political practice of those years. But paradoxically, what could then have been considered Pasolini's outdatedness has been transformed, since his death, more and more, until today, into a very strong, singular topicality.

It is as if, after the censorship and ostracism he suffered during his lifetime, Pasolini has now become a constant and inescapable presence, almost as a sort of reparative compensation. It would be nice if the occasion of Pasolini's centenary were to be grasped above all by the younger generation, by those young people to whom Pasolini dedicated so many of his reflections and to whom he continued - and continues today - to speak. Unfortunately, he is still an author that is rarely encountered at school (as, moreover, are almost all his contemporaries). Young people know Pasolini's name and maybe some of his quotes found on the web or on social networks. But they often ignore his work: his poems, his novels, his journalistic interventions, his films.

Now is the time to discover them.